44 Views

1

View In My Room

Photography, Digital on Paper

Size: 39.4 W x 53.1 H x 0.1 D in

Ships in a Tube

44 Views

1

ABOUT THE ARTWORK

DETAILS AND DIMENSIONS

SHIPPING AND RETURNS

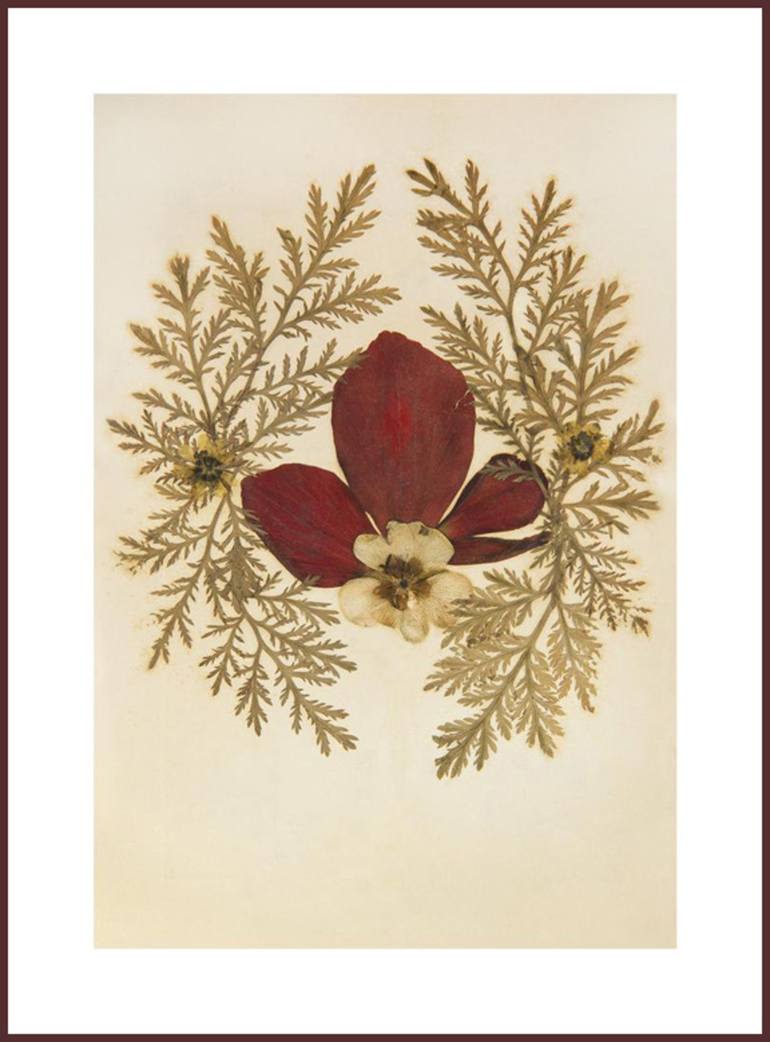

Orit Ishay 1917, untitled #01, 2012 still photography, archival inkjet print 135x100 cmnumbered and signed Edition: 5 +2AP Souvenirs are not unlike passports. They are more then just a thing, image or text. They are something you bring when you go somewhere. So they have a lot to do with a moment o...

Year Created:

2012

Subject:

Mediums:

Photography, Digital on Paper

Rarity:

Limited Edition of 5

Size:

39.4 W x 53.1 H x 0.1 D in

Ready to Hang:

Not Applicable

Frame:

Not Framed

Authenticity:

Certificate is Included

Packaging:

Ships Rolled in a Tube

Delivery Cost:

Shipping is included in price.

Delivery Time:

Typically 5-7 business days for domestic shipments, 10-14 business days for international shipments.

Returns:

The purchase of photography and limited edition artworks as shipped by the artist is final sale.

Handling:

Ships rolled in a tube. Artists are responsible for packaging and adhering to Saatchi Art’s packaging guidelines.

Ships From:

Israel.

Need more information?

Need more information?

Orit Ishay

Israel

Why Saatchi Art?

Thousands of

5-Star Reviews

We deliver world-class customer service to all of our art buyers.

Global Selection of Original Art

Explore an unparalleled artwork selection from around the world.

Satisfaction Guaranteed

Our 14-day satisfaction guarantee allows you to buy with confidence.

Support Emerging Artists

We pay our artists more on every sale than other galleries.