VIEW IN MY ROOM

Casablanca Print

Mexico

Select a Material

Fine Art Paper

Select a Size

10 x 8 in ($40)

Add a Frame

White ($80)

Artist Recognition

Artist featured in a collection

About The Artwork

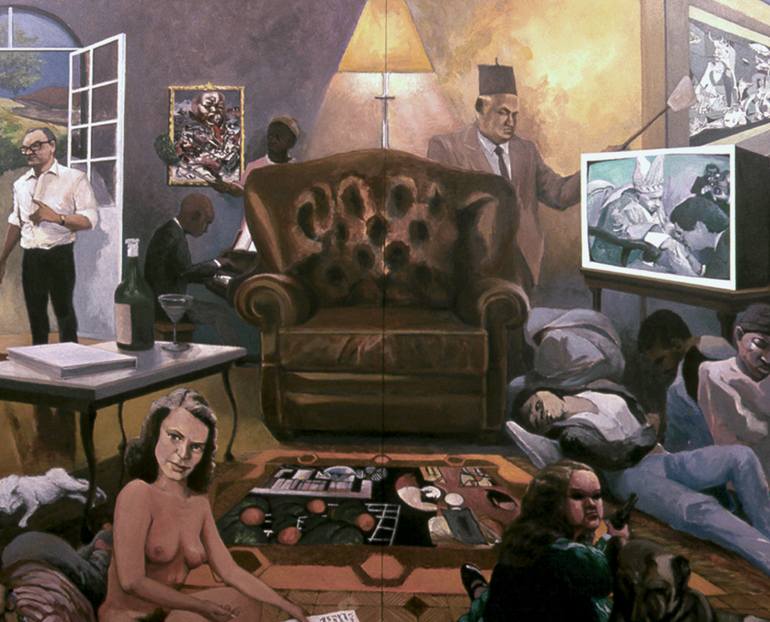

"Casablanca" 2003 Acrylic on panel Painting is a diptych (both panels permanently attached with screws inside frame structure; piece ships that way) 48 x 59.25 x 2 in., outside dimensions of frame; the painting, which is “floated” inside the frame, measures slightly less (approximately 46 x 57.25 in.). This piece represents a confluence of historical time and is a meditation on how the “apolitical” character of cultural spaces and art promotion, such as that represented by the MoMA in New York, allows for odd juxtapositions of intensely political expressions of culture with completely non-political or anti-political expressions. Included (as examples of “political” art from the MoMA collection) are copies David Alfaro Siqueiros’s “Eco de un grito” (Echo of a Scream) and Picasso’s “Guernica,” and, as an example of non-political or anti-political art, Matisse’s “Les Marocains” (The Moroccans), reproduced as a floor rug that sits comfortably in front of the central easy chair. The easy chair itself is another reference to Matisse, specifically to his notion that the work of art ought to be like a comfortable armchair for the tired businessman or the man of letters to relax into after a hard day’s work. This statement appears (in French) on the paper the nude model holds in her hand. « L’œuvre d’art doit être pour l’homme d’affaires aussi bien que pour l’artiste de lettres un calmant cérébral, quelque chose d’analogue à un bon fauteuil qui le délasse de ses fatigues physiques. » —Matisse (“The work of art ought to be a cerebral sedative for the businessman and the man of letters, something akin to a comfortable armchair in which to relax from his physical weariness.” —Matisse). Obviously, there are other artists who feel quite differently about art, about what it ought to be and about what the role of the artist in society should be. However, even Matisse himself, curled up on the floor beside the model, may be putting in doubt his own declaration of artistic principles: he is flipping through a catalogue of reproductions of the works of Edouard Manet, open to a double page that shows two fairly “non-apolitical” works by that fairly “non-apolitical” artist: on one side, a version of Manet’s “L’exécution de Maximilien” (The Execution of the Emperor Maximilian) and on the other, his portrait of the writer Emile Zola (from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris). While the motive for the portrait of Zola was Manet’s personal appreciation for the writer’s having expressed his support for the painter’s work, and predated by many years Zola’s most famous political position-taking—his “J’accuse,” against the anti-Semitic railroading of Dreyfus by the French government and military authorities—, by the time Matisse had reached the age at which I have portrayed him here, this most famous aspect of Zola’s dissidence had long been a well-known historical fact. The businessmen “owners” of the MoMA, David and Nelson Rockefeller, for whom, presumably, the art collection serves as their own personal easy chair, are engaged in conversation together, while Señor Ferrari (the fat businessman from the movie “Casablanca” who takes Rick’s Café Americain off his hands as the movie builds towards its climax, explaining that his shipments of contraband cigarettes were always a few cartons short because of “handling charges, my dear fellow, handling charges”), uses his fly swatter behind the empty armchair “work of art.” Silvio Berluscone, then the Prime Minister of Italy, smiles complacently, standing next to a television set (that may be tuned in to one of the stations from his media empire) on which is seen the image of José María Aznar, then the conservative Partido Popular’s leader of the Spanish government, abjectly and devotedly kissing the papal ring during an official state visit to the Vatican. An oil-rich Middle eastern potentate admires the Picasso painting, ensconced behind the garishly greenish bullet-proof glass that was installed to protect it from Basque separatist attacks when the MoMA first returned it to Spain, and it was exhibited in Madrid’s Casón del Buen Retiro. I saw it there, in January 1982, several months after its installation, and was impressed with how “precious” it had become in its new setting, amid the 17th century building’s florid ceiling murals and the members of the armed Guardia Civil militia who stood guard over this newly acquired “national treasure.” It was quite a difference from how I remember being able to see it at the MoMA, during the years I attended art school in New York, where the painting had an immediacy and directness owing to its visible accessibility, at the top of the stairs by the third floor landing. But such has been the fate of much great art in our time, reduced, as in eras of monarchical privilege, to levels of ridiculous “preciousness,” often rendered essentially invisible, inaccessible even for viewing, except by the ultra-rich who can buy it and hide it away, tax- and duty-free, in luxurious climate-controlled storage facilities at freeports in any number of fiscal paradises scattered throughout the world until they are inclined to sell it for exhorbitant profit to someone else likely to do the same thing with (and to) the work. On the floor around the TV, there are several recent African refugees from current Moroccan reality, migrants recently disembarked in Spain after crossing the Mediterranean. They are being detained by María Bárbola, the Austrian “court dwarf” in 17th century Madrid, from Velázquez’s “Las meninas.” A pistol in her hand, she has the drop on the lethargic and unthreatening foreigners, and therefore little need that the dog from the famous Prado painting should rise out of his customary placidity to help guard the court and defend royal privilege against the illegal arrival of these dejected and exhausted refugees.

Details & Dimensions

Print:Giclee on Fine Art Paper

Size:10 W x 8 H x 0.1 D in

Size with Frame:15.25 W x 13.25 H x 1.2 D in

Frame:White

Ready to Hang:Yes

Packaging:Ships in a Box

Shipping & Returns

Delivery Time:Typically 5-7 business days for domestic shipments, 10-14 business days for international shipments.

Handling:Ships in a box. Art prints are packaged and shipped by our printing partner.

Ships From:Printing facility in California.

Have additional questions?

Please visit our help section or contact us.

Mexico

Dale Kaplan (b. 1956) grew up in a rural town near Boston MA, attending public schools, and later studied at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn NY and Cornell University in Ithaca NY (BFA ‘81). He was awarded the MCC (Massachusetts Cultural Council) Artist’s Grant in 2000, in recognition of artistic excellence in Painting. In the late 1980s he established a studio in Guadalajara and has divided his life and work between Mexico and the U.S. ever since. Exhibiting professionally in both countries, as well as in Canada, his works are in numerous private collections. Also active as an art critic, essayist and translator, since 1999 Kaplan has published original writing in several Spanish-language newspapers, magazines and online sites, and has various book credits as a translator. His texts, photographic essays, and reproductions of his paintings and graphic works, have appeared in numerous publications, as well as on book and CD covers, and his work has been included in historical exhibitions and published anthologies focused on the art produced in the Mexican state of Jalisco. In both imagery and texts, Kaplan’s work takes to heart Noam Chomsky’s definition of the responsibility of the intellectual: “to tell the truth and expose lies.” ______________________________________ARTIST'S STATEMENT_________________________ The driving force behind my artmaking is the conviction that painting has as much or more potential for intellectual expression as that which is generally attributed only to verbal language. My interest in critical thought about sociocultural, political, and power relationships, as well as in occasionally using satire and art-historical references to take some air out of the overblown types who rule with a "whim of iron"—are essentially the same as they were before coming to Mexico, and my frequent forays into language play and playing with imagery are the kinds of play I take seriously. In Mexico, though, like on the African plains, one plays, like small game, with one eye out for large predators who are always lurking just off to the side. Journalism can be a most dangerous game in this country, as can be practicing social critique or just openly expressing one's honest opinion. In life, risks must be taken, though, despite dubious "risk-reward" ratios. Many of my works have a backstory related to in-depth research on topics of concern to me, sometimes utilizing investigative techniques such as Freedom of Information requests.

Artist Recognition

Artist featured by Saatchi Art in a collection

Thousands Of Five-Star Reviews

We deliver world-class customer service to all of our art buyers.

Global Selection

Explore an unparalleled artwork selection by artists from around the world.

Satisfaction Guaranteed

Our 14-day satisfaction guarantee allows you to buy with confidence.

Support An Artist With Every Purchase

We pay our artists more on every sale than other galleries.

Need More Help?