VIEW IN MY ROOM

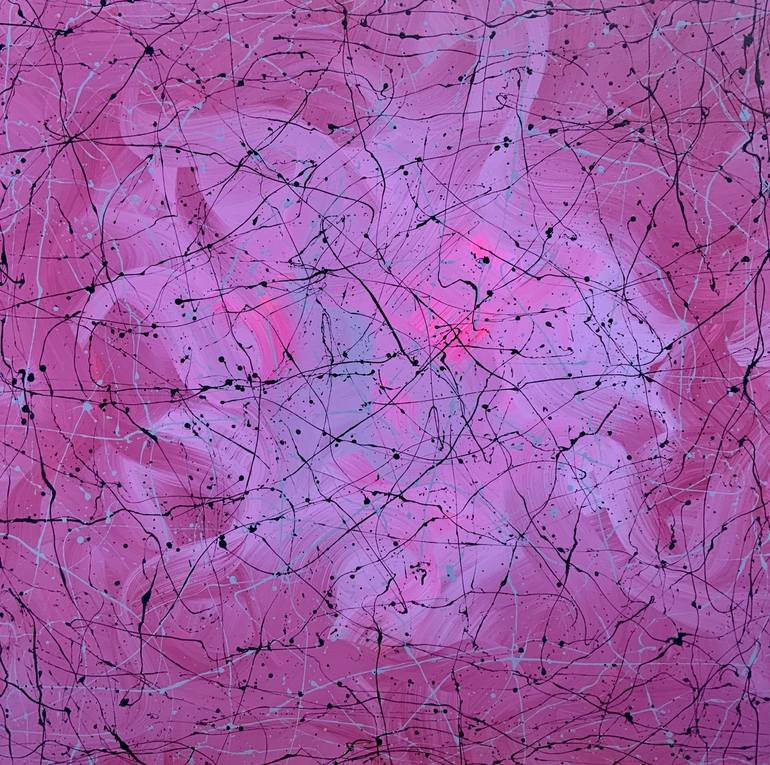

Let Your Mind Alone! Painting

Painting, Acrylic on Canvas

Size: 48 W x 48 H x 1.5 D in

Ships in a Crate

Shipping included

14-day satisfaction guarantee

Artist Recognition

Artist featured in a collection

About The Artwork

"Has anybody got any more sets of specific disciplines? If anybody has, they've got to be pretty easy ones if I am going to wake up and live. It's mighty comfortable dozing here and waiting for the end." "In Chapter VI, which is entitled 'Using What You've Got’, Dr. Mursell deals with the problem of how to learn and how to make use of what you have learned. He believes, to begin with, that you should learn things by doing them, not by just reading up on them. In this connection he presents the case of a young man who wanted to find out 'how to conduct a lady to a table in a restaurant’. Although I have been gored by a great many dilemmas in my time, that particular problem doesn't happen to have been one of them. I must have just stumbled onto the way to conduct a lady to a table in a restaurant. I don't remember, as a young man, ever having given the matter much thought, but I know that I frequently worried about whether I would have enough money to pay for the dinner and still tip the waiter. Dr. Mursell does not touch on the difficult problem of how to maintain your poise as you depart from a restaurant table on which you have left no tip." "There is a curious tendency on the part of the How-to-Live men to make things hard. It recurs time and again in the thought-technique books. In this same Chapter VI there is a classic example of it. Dr. Mursell recounts the remarkable experience of a professor and his family who were faced with the necessity of reroofing their country house. They decided, for some obscure reason, to do the work themselves, and they intended to order the materials from Sears, Roebuck. The first thing, of course, was to find out how much roofing material they needed. ‘Here’, writes Dr. Mursell, 'they struck a snag’. They didn't, he points out, have a ladder, and since the roof was too steep to climb, they were at their wits' end as to how they were going to go about measuring it. You and I have this problem solved already: we would get a ladder." "Thus, in embroidering the theme that imagination can help you with your fellow-workers, she writes, 'When you have seen this, you can work out a code for yourself which will remove many of the irritations and dissatisfactions of your daily work. Have you ever been amused and enlightened by seeing a familiar room from the top of the stepladder; or, in mirrors set at angles to each other, seen yourself as objectively for a second or two as anybody else in the room? It is that effect you should strive for in imagination.' Here again I cannot hold with the dear lady. The nature of imagination, as she describes it, would merely terrify the average man. The idea of bringing such a distorted viewpoint of himself into his relation with his fellow-workers would twist his personality laboriously out of shape and, in the end, appall his fellow-workers. Men who catch an unfamiliar view of a room from the top of a stepladder are neither amused nor enlightened; they have a quick, gasping moment of vertigo which turns rapidly into plain terror. No man likes to see a familiar thing at an unfamiliar angle, or in an unfamiliar light, and this goes, above all things, for his own face. The glimpses that men get of themselves in mirrors set at angles to each other upset them for days. Frequently they shave in the dark for weeks thereafter." "For true guidance and sound advice in the business world we find, I think, that the success books are not the place to look, which is pretty much what I thought we would find all along." "'11. Set yourself twelve instructions on pieces of paper, shuffle them, and follow the one you draw. Here are a few samples: Go twelve hours without food. Stay up all night and work. Say nothing all day except in answer to questions.' In that going twelve hours without food, do you mean I can have drinks? Because if I can have drinks, I can do it easily. As for staying up all night and working, I know all about that: that simply turns night into day and day into night. I once got myself into such a state staying up all night that I was always having orange juice and boiled eggs at twilight and was just ready for lunch after everybody had gone to bed. I had to go away to a sanitarium to get turned around. As for saying nothing all day except in answer to questions, what am I to do if a genial colleague comes into my office and says, 'I think your mother is one of the nicest people I ever met' or 'I was thinking about giving you that twenty dollars you lent me' Do I just stare at him and walk out of the room? I lose enough friends, and money, the way it is.” "If you persist, you will soon solve anything at all, no matter how impossible. That way, of course, lies madness, but I would be the last person to say that madness is not a solution.” from ‘Let Your Mind Alone! And Other More or Less Inspirational Pieces’ by James ‘cuz’ Thurber Description: The first half of this book dissects (with snarky glee) Depression-era self-help books. Oddly enough, self-help books haven't really changed all that much in 70-plus years. There are none so pompous as those who would tell others how to behave, and Thurber skewers them deliciously. The second half of the book contains a collection of essays, with some short fiction and some commentary, and includes Thurber's memories of the time he spent in France during and after the first World War. Source: fadedpage.com James Grover Thurber (December 8, 1894 – November 2, 1961) was an American cartoonist, author, humorist, journalist, playwright, and celebrated wit. He was best known for his cartoons and short stories, published mainly in The New Yorker and collected in his numerous books. Thurber was one of the most popular humorists of his time and celebrated the comic frustrations and eccentricities of ordinary people. His works have frequently been adapted into films, including The Male Animal (1942), The Battle of the Sexes (1959, based on Thurber's "The Catbird Seat"), and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (adapted twice, in 1947 and in 2013). From 1913 to 1918, Thurber attended Ohio State University where he was a member of the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity and editor of the student magazine, the Sun-Dial. It was during this time he rented the house on 77 Jefferson Avenue, which became Thurber House in 1984. He never graduated from the university because his poor eyesight prevented him from taking a mandatory Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) course. In 1995 he was posthumously awarded a degree. From 1918 to 1920, Thurber worked as a code clerk for the United States Department of State, first in Washington, D.C. and then at the embassy in Paris. On returning to Columbus, he began his career as a reporter for The Columbus Dispatch from 1921 to 1924. During part of this time, he reviewed books, films, and plays in a weekly column called "Credos and Curios", a title that was given to a posthumous collection of his work. Thurber returned to Paris during this period, where he wrote for the Chicago Tribune and other newspapers. Move to New York In 1925, Thurber moved to Greenwich Village in New York City, getting a job as a reporter for the New York Evening Post. He joined the staff of The New Yorker in 1927 as an editor, with the help of E.B. White, his friend and fellow New Yorker contributor. His career as a cartoonist began in 1930 after White found some of Thurber's drawings in a trash can and submitted them for publication; White inked-in some of these earlier drawings to make them reproduce better for the magazine, and years later expressed deep regret that he had done such a thing. Thurber contributed both his writings and his drawings to The New Yorker until the 1950s. Marriage and family Thurber married Althea Adams in 1922, but the marriage, as he later wrote to a friend, devolved into “a relationship charming, fine, and hurting.” The marriage ended in divorce in May 1935. They lived in Fairfield County, Connecticut, with their daughter Rosemary (b. 1931). He married Helen Wismer (1902–1986) in June 1935. After meeting Mark Van Doren on a ferry to Martha's Vineyard Thurber began summering in Cornwall, along with many other prominent artists and authors of the time. After three years of renting Thurber found a home, which he referred to as "The Great Good Place." Death Thurber's behavior became erratic and unpredictable in his last year. At a party hosted by Noël Coward, Thurber was taken back to the Algonquin Hotel at six in the morning. Thurber was stricken with a blood clot on the brain on October 4, 1961, and underwent emergency surgery, drifting in and out of consciousness. The operation was initially successful, but Thurber died a few weeks later, on November 2, aged 66, due to complications from pneumonia. The doctors said his brain was senescentfrom several small strokes and hardening of the arteries. His last words, aside from the repeated word "God", were "God bless... God damn", according to his wife, Helen. Source: WIkipedia

Details & Dimensions

Painting:Acrylic on Canvas

Original:One-of-a-kind Artwork

Size:48 W x 48 H x 1.5 D in

Frame:Not Framed

Ready to Hang:Not applicable

Packaging:Ships in a Crate

Shipping & Returns

Delivery Time:Typically 5-7 business days for domestic shipments, 10-14 business days for international shipments.

Handling:Ships in a wooden crate for additional protection of heavy or oversized artworks. Crated works are subject to an $80 care and handling fee. Artists are responsible for packaging and adhering to Saatchi Art’s packaging guidelines.

Ships From:United States.

Have additional questions?

Please visit our help section or contact us.

I’m (I am?) a self-taught artist, originally from the north suburbs of Chicago (also known as John Hughes' America). Born in 1984, I started painting in 2017 and began to take it somewhat seriously in 2019. I currently reside in rural Montana and live a secluded life with my three dogs - Pebbles (a.k.a. Jaws, Brandy, Fang), Bam Bam (a.k.a. Scrat, Dinki-Di, Trash Panda, Dug), and Mystique (a.k.a. Lady), and five cats - Burglekutt (a.k.a. Ghostmouse Makah), Vohnkar! (a.k.a. Storm Shadow, Grogu), Falkor (a.k.a. Moro, The Mummy's Kryptonite, Wendigo, BFC), Nibbler (a.k.a. Cobblepot), and Meegosh (a.k.a. Lenny). Part of the preface to the 'Complete Works of Emily Dickinson helps sum me up as a person and an artist: "The verses of Emily Dickinson belong emphatically to what Emerson long since called ‘the Poetry of the Portfolio,’ something produced absolutely without the thought of publication, and solely by way of expression of the writer's own mind. Such verse must inevitably forfeit whatever advantage lies in the discipline of public criticism and the enforced conformity to accepted ways. On the other hand, it may often gain something through the habit of freedom and unconventional utterance of daring thoughts. In the case of the present author, there was no choice in the matter; she must write thus, or not at all. A recluse by temperament and habit, literally spending years without settling her foot beyond the doorstep, and many more years during which her walks were strictly limited to her father's grounds, she habitually concealed her mind, like her person, from all but a few friends; and it was with great difficulty that she was persuaded to print during her lifetime, three or four poems. Yet she wrote verses in great abundance; and though brought curiosity indifferent to all conventional rules, had yet a rigorous literary standard of her own, and often altered a word many times to suit an ear which had its own tenacious fastidiousness." -Thomas Wentworth Higginson "Not bad... you say this is your first lesson?" "Yes, but my father was an *art collector*, so…"

Artist Recognition

Artist featured by Saatchi Art in a collection

Thousands Of Five-Star Reviews

We deliver world-class customer service to all of our art buyers.

Global Selection

Explore an unparalleled artwork selection by artists from around the world.

Satisfaction Guaranteed

Our 14-day satisfaction guarantee allows you to buy with confidence.

Support An Artist With Every Purchase

We pay our artists more on every sale than other galleries.

Need More Help?